The OGM Interactive Edition – Summer 2023 – Read Now!

View Past IssuesIn the early 1800s wood was the primary energy source throughout much of the world: but this could not last as populations grew, industrialization accelerated, and forests were depleted—especially on islands like Britain. Then came coal to the rescue, and the forests were given a reprieve. For a time coal was king as a heat source, but we still needed a flammable oil for our lamps. And, to get it we (sadly) took to slaughtering some the most magnificent animals the world has ever seen: the great whales.

Herman Melville captured the period of Whaling for oil, in his iconic “Moby Dick”, which happened to be inspired by the true story of the Essex: a whaler out of Nantucket that was sunk (in 1820) by an anguished sperm whale.

Herman Melville captured the period in his iconic “Moby Dick”, which happened to be inspired by the true story of the Essex: a whaler out of Nantucket that was sunk (in 1820) by an anguished sperm whale. A telling facet of the Essex debacle is that she met her end in the Pacific Ocean—suggesting that whales were already scarce in the Atlantic. Indeed, many whale species would likely have been hunted to extinction in the 1800s, if not for the efforts of a Nova Scotian geologist named Abraham Gesner: for it was Gesner who (in 1846) extracted an oily liquid from coal-dust by heating it in an airtight container. He called his new invention kerosene, and it proved to be such an excellent lamp-oil that he effectively saved the whales. And aren’t we glad he did!

The most important oil well ever drilled was sunk in the middle of the wooded landscape of northwest Pennsylvania in August 1859. It is known as the Drake Well, after “Colonel” Edwin L. Drake, the man responsible for the well – who had no knowledge whatsoever of either geology or drilling.

Soon came the beginnings of the modern oil industry with Colonel Drake’s well in Pennsylvania (in 1859) followed by discoveries over the coming decades in Texas, California, Alberta, Saudi Arabia, etc.: and, with this, the world was presented with an abundant supply of the most versatile energy source we had ever known. In relatively short order came oil-stoves, cars, planes, nylon, plastics, and thousands of other products that we now count essential. Indeed, it can be well argued that modern civilization could not have come into existence without the petroleum industry. But, as it often goes, too much of a good thing can also be a bad thing. For, as we burned increasing amounts of fossil fuels over the decades while dumping the waste gases (particularly CO2) into the atmosphere, it was inevitable that there would be consequences.

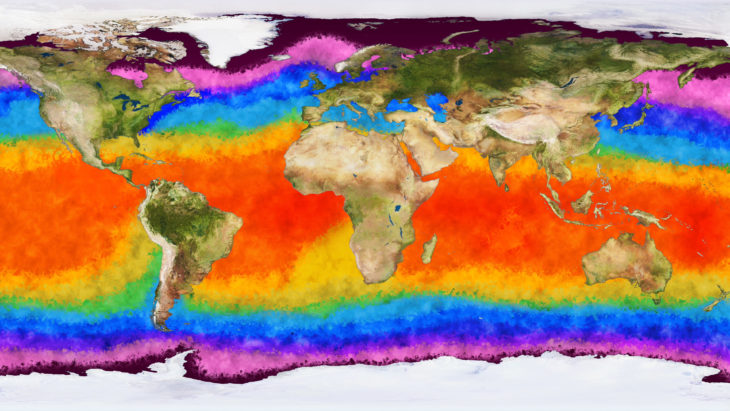

THE WATER TEMPERATURE: CO2 is a greenhouse gas that lags a long time in the atmosphere. Unlike water vapour (the most prevalent greenhouse gas) it does not condense and fall as rain after a few days and thus, tends to build up in the atmosphere over time—leading to an increasing greenhouse effect and warming climate.

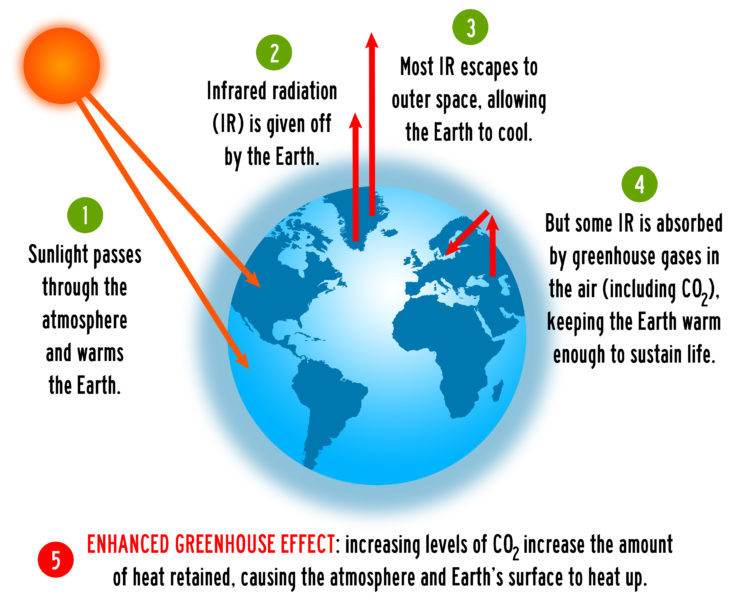

The global warming story is now ubiquitous news fodder, so I will here address only the essentials. The bottom line is that CO2 is a greenhouse gas that lags a long time in the atmosphere. In other words, unlike water vapour (the most prevalent greenhouse gas) it does not condense and fall as rain after a few days; and, thus, tends to build up in the atmosphere over time—leading to an increasing greenhouse effect and warming climate. But why worry? After all, the geological and historical records show that the climate has always changed. What’s different this time? The major difference now is two-fold:

(1) We now have almost 8 billion people settled into specific regions that are currently capable of providing them with adequate food and water; and,

(2) We are changing the climate at a rate that is unprecedented in human history (and rare in Earth history).

Thus, the problem arises not from the change itself, which is inevitable, but from the rate and degree of change.

Modern humans have been around for about 200,000 years and, during that time, have migrated in response to major changes in climate. But in ancient times we were small in number and did not have to deal with hard borders backed by weapons of mass destruction. And if the climate changed gradually, over the course of a few thousand years, we had plenty of time to migrate and adapt. The most recent big change came at the end of the last ice age and involved an average global temperature rise of 4 to 5 degrees Celsius over about 7000 years. By contrast, unless we severely curtail our greenhouse exhaust, we are looking at a similar temperature change over the course of a few decades: which means we will change the ecosystem at a rate that will severely challenge or exceed our (and many other species) ability to adapt. Billions may lose access to water and the ability to feed themselves, and some large regions across the tropics may become uninhabitable because of extreme heat.

How will people who have lost everything react? Predictably, desperate people will take desperate action. And when billions become desperate, the niceties of what we call civilization are unlikely to remain a priority. After all, would you be much concerned with “the rule of law” if you were dying of thirst, heat, or starvation?

A little background information will be useful to clear up any lingering misconceptions. The atmosphere contains about 3200 billion tons of CO2 and is gaining about 40 billion tons (per year) from human activity along with about .3 billion tons from volcanoes. This is “new carbon” (i.e. not part of the normal cycle) that is being extracted from the ground and injected into a system that was in a quasi-stable equilibrium. And just as pouring sand onto one side of a balanced set of scales will eventually send it tumbling, constantly adding CO2 to the atmosphere will result in major changes.

Fortunately, most of the CO2 we emit is absorbed by the ocean: otherwise, we’d see a much more rapid change in the climate. But, unfortunately, increasing the amount of carbon in the ocean makes it more acidic through the creation of carbonic acid. And, among other things, a more acidic ocean makes it more difficult for organisms to grow shells and exoskeletons. Of greatest concern, are certain species of shelly phytoplankton—which may become incapable of reproduction. The fact that these creatures lie at the base of the food chain means that their reduction or extinction would put all marine species at risk; and, the fact that they provide about one-quarter of our breathable oxygen through photosynthesis puts all air-breathing organisms (including us) at risk. Although ocean acidification is yet poorly understood, it may present an even greater danger than a hotter climate.

Of greatest concern, are certain species of shelly phytoplankton—which may become incapable of reproduction. The fact that these creatures lie at the base of the food chain means that their reduction or extinction would put all marine species at risk; and, the fact that they provide about one-quarter of our breathable oxygen through photosynthesis puts all air-breathing organisms (including us) at risk. Although ocean acidification is yet poorly understood, it may present an even greater danger than a hotter climate.

So what are we to do? For starters, we need to stop calling each other names such as “alarmists” and “deniers”. Assigning ourselves to opposing camps and attaching personal identity to a political party or point of view is to subvert our ability to think critically, and more likely to create barriers to gainful dialogue than to be helpful. For, if we are to have any hope of solving problems that require technical insight and effectual action, we must strive for a dispassionate appraisal of the facts and their significance. And, as we are undeniably passionate by nature, we must harness that passion toward finding and implementing the best possible solutions rather than fueling conflict. For inspiration, we may look to the inhabitants of the International Space Station: who have similar needs within a smaller ecosystem.

By now, it should be fairly clear where I stand on the issue. However, I must admit that for most of my career I hardly gave a second thought to global warming. This changed when I became a part-time trainer in the oil and gas industry and was stirred to become more informed by the astute questions of students. In effect, I went back to school; and after extensive study of the relevant physics, the facts became clear and the evidence overwhelming. Today I am most definitely alarmed by what I am seeing writ large in recent weather, polar ice-cover, glacial retreat, species migration, coral bleaching, and wild-fire patterns. And I am genuinely fearful of what our kids and grandkids will likely face if we fail to take necessary action.

But why believe me? After all, I’m no climatologist. Fair point! On that note, my best advice is to search the web for a concise summary-document called “Climate Change: Evidence and Causes” which was issued in 2015 by two of the most esteemed scientific organizations in the world: namely The Royal Society and The US Academy of Sciences. If you don’t consider these organizations (along with NASA and NOAA) to be scientifically competent and credible, then there is little that I, or anyone, can say that will much matter.

READ PDF HERE: https://royalsociety.org/-/media/Royal_Society_Content/policy/projects/climate-evidence-causes/climate-change-evidence-causes.pdf

It is oh so human to get caught in the dramas of our daily lives: but, for a moment, let’s pan back and take a look at the bigger picture. Throughout history, each generation is likely to face some major test. The great challenge of the twentieth century was to extend human freedom and fight tyranny: and we can be eternally grateful to our parents and grandparents for their courage and sacrifice on that front. Although we must remain vigilant against tyrants, today our greatest challenge is to preserve the ecosystem that sustains us and our fellow creatures.

We must all do our bit as individuals. For example, we can switch to energy efficient light-bulbs, choose foods with a lower carbon footprint, and (where practicable) allow our employees to work from home and do meetings and presentations by video-link rather than driving across town or flying half-way around the world. Governments can increase awareness and encourage change by requiring the labeling of food, clothing, and other products to indicate their relative environmental footprint. And, as each individual “green-act” is a small step, billions of small steps add up to significant progress. However, beyond our individual choices, we must also cooperate across cultural and political boundaries at an unprecedented scale: with industrialized countries sharing technology and helping developing countries advance through environmentally sustainable means. And, in this formidable quest, the oil industry is well positioned to play a major role—and to profit handsomely in the process.

At present fossil fuels (including coal, oil, and natural gas) source about 85% of humanity’s energy consumption, so we have a long way to go before achieving 100% renewable. Indeed, we are likely to need fossil fuels for several decades to come. As it now stands, most of the CO2 from fossil fuel combustion is being blown out our chimneys, tail-pipes, and smokestacks. Yet, our best models indicate that the oil industry will have to leave most of its hard-won assets in the ground if we are to avoid catastrophic climate change. However, there is an angle that allows fossil fuel companies to monetize their reserves and meet carbon targets: it’s called carbon capture and sequestration (CCS).

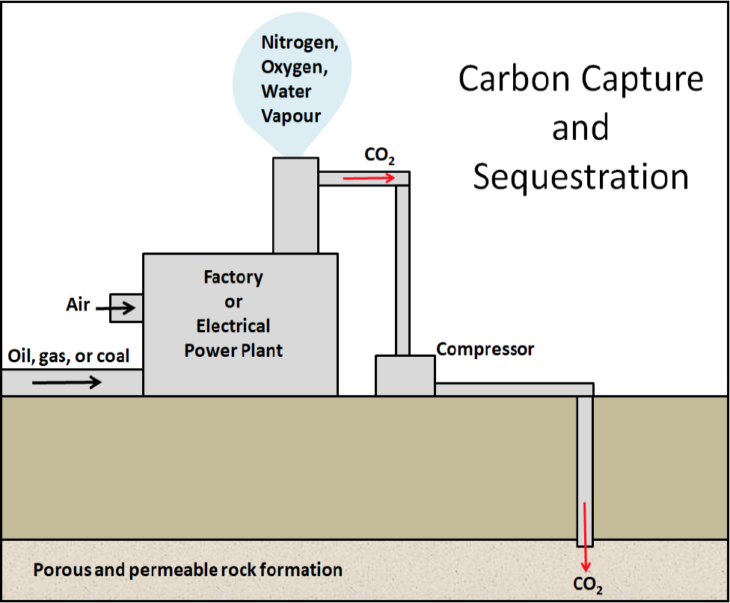

There are a variety of technical approaches (which I won’t go into here); but CCS essentially equates to removing CO2 from our smoke-stack exhaust, compressing it for delivery to injection sites, and pumping it into porous/permeable underground rock formations for permanent storage. But, what of car and chimney exhaust? Well, we can’t effectively capture exhaust from a billion cars or houses: so this means we must go all-in for electric cars and electric heat. As for the additional electricity needed to run all these cars and heaters, we are to get it by burning fossil fuels at centralized generation hubs (instead of in engines and furnaces), while applying CCS to prevent further air pollution. In some cases, it may even be feasible to use CCS to remove carbon from the atmosphere—by burning fast-growing vegetation to power generators and sequestering the carbon.

No doubt, there remain major technical and cost challenges to CCS. For example, it requires more fuel to capture and compress the carbon, than to dump it into the atmosphere. On top of this, there are increased capital costs in building the plant, plus the cost of piping or trucking the CO2 to a disposal well and pumping it into the ground. However, given that hydrocarbons are to be converted directly to electricity nearer their source-points, some of the new expenses are offset by the reduced need for transportation, refining, and storage. All things considered, it is likely that the price of electricity will go up in the short term. However, increased electrical rates would be offset by the fact that electric motors are about four times as efficient as internal combustion engines, and electric heaters are 100% efficient. Indeed, at current electricity prices, electric car owners in North America typically spend only about US$500 per year on fuel. So over the long haul, as we absorb the capital and research costs, the price of energy is likely to trend lower. And, in any case, shouldn’t the proper management of our waste products be built into the cost of doing business?

In tackling the extra costs for CCS, governments must provide effective tax incentives and support research toward less expensive methods. Although many on the political left would decry any initiative that allows the fossil fuel industry to continue (using CCS or otherwise)—to have any hope of achieving the climate goals we need to be realistic. To quote MIT’s Howard Herzog, author of the 2018 book “Carbon Capture”: “The right underestimates the magnitude of the climate change problem, while the left underestimates the magnitude of the climate change solution”.

Beyond the infrastructure expenditures, we are going to need international agreements to facilitate the marketing of the additional electricity that will be generated in a CCS economy. For example: If Alberta were to start burning its hydrocarbons at electrical generation hubs in-province and building additional power-lines instead of pipelines to reach North American markets, the companies would need assurance that the provinces and states are switching to electric cars and heat at a rate that provides a market for the new electricity. As for oil from offshore fields, such as the Grand Banks, it would be shipped to locations with adequate CCS infrastructure and turned into electricity.

In a nutshell, just as the fossil fuel industry helped save the forests and the whales, it can also play an important role in getting us safely through the transition to sustainable (and reliable) energy. The oil industry is well positioned on this front, because it has already finessed most of the CCS-related technologies, including drilling, pipeline construction, compression, injection, and reservoir monitoring. At present, CCS is being applied at only a couple of dozen locations worldwide, but it is being promoted for broader application to fight climate change by major oil companies (including Exxon, Shell, and BP) as well as environmental groups (including the Nature Conservancy and the Environmental Defense Fund).

In several of the existing CCS projects, the captured CO2 is being injected into oil reservoirs to increase production (by lowering the viscosity of the oil so that it flows more easily). With more carbon capture, there will be a ready supply for enhanced oil recovery in many existing fields: which remains inbounds as long as the carbon is not destined for the atmosphere. Nevertheless, cost remains a serious challenge to expanding CCS to the scale needed to make a difference in the larger game, and so the said tax incentives and directed research are obligatory. Yet in weighing these costs of action, we must also weigh the cost of inaction: which until recently was rarely included in the economic equation.

In closing, I must emphasize that CCS is not the sole solution, but must be part of a greater whole that will include: improved efficiencies; low-carbon farming and manufacturing; afforestation; reforestation; wind, wave, tidal, solar, geothermal, and nuclear power; unforeseen technologies; greater societal awareness; and more enlightened politics.

Overcoming the technical, economic, and political obstacles to address climate change and ocean acidification will require a strenuous international effort—akin to what “the greatest generation” exacted to preserve our freedom. In this regard, even less populous countries (like Canada) can punch far above their weight through technological and geopolitical leadership. On a positive note, we well know that any great technological and societal movement within a free enterprise system also brings great economic opportunity. And it is in this spirit that, as one of the world’s largest and most technically savvy industries, we must engage the great challenge of our age with a genius and determination that will echo through the ages and provide a leg-up to those who must build on what we’ve begun. For in the final accounting it will be our children and grandchildren who will reap our harvest, and pass judgement on how we responded when history came calling and put the fate of civilization in our hands. We must not fail.

Phonse Fagan, is a petroleum geophysicist in St. John’s Newfoundland and owner of A.J. Fagan Consulting Inc. and Petro-Ed, which offers short courses to the oil and gas industry (www.petro-ed.com).

Did you enjoy this article?