by Tina Olivero

| No comment

Published on January 4th, 2014

Broen Som Binder Oss Sammen - A Bridge That Connects Us

What two places on the planet have bake apples (cloud berries), northern lights, abandoned fishing villages, fjords, harsh northern winters, majestic summers, and a booming oil industry offshore? Yes, that’s right—Newfoundland and Norway.

Mother Norway

Understanding the history of Norway gives us insight into the paralleling success of Newfoundland. Albeit twenty years ahead of their counterpart, Norwegians have been a progressive mother to Newfoundlanders, offering them direction and guidance from areas like fish stock recovery all the way to government involvement in oil plays. The parallels are unmistakable between Newfoundland and Norway, and even their respective capital cities’ downtown cores in Stavanger and in St. John’s look related. Small hotels, shops, and pubs, nestled into a hidden harbor, decorate the colorful landscape. While separated by continents, oceans, and thousands of miles, these two regions remain remarkably the same.

The Cod Father

On July 2, 1992, the Canadian government imposed a moratorium on the northern cod fishery along the country’s eastern fishing grounds. Decades of overfishing had depleted cod stocks, and government officials hoped the moratorium would allow the species to rebuild and combat the effects of severe foreign overfishing.

This moratorium ended almost 500 years of fishing activity in Newfoundland and Labrador, where it put 30,000 people out of work. Fish plants closed, boats remained docked, and hundreds of coastal communities that had depended on fishery for generations watched the economic and cultural mainstay disappear overnight.

In Norway, fishery has been a major industry as well. Norway’s geographical characteristics, the long coastline together with climatic factors, have made the country extremely well suited for fishing. Like Newfoundland, Norway is a major European fishery nation, and has been for centuries. Paralleling Newfoundland, Norway has experienced a decline in their fishery with cod and herring being at the core of the industry.

With the moratorium in effect, Newfoundland and Norway faced an economic turn of events that would shape the future in unimaginable ways. Each region experienced fishery falling away, and the petroleum industry began edging into the economic space to provide what fishery no longer could. Oil became the new economic stimulator that set the stage for many years to come.

Vikings Arrive In Newfoundland

More than 1,200 years ago, Vikings from Norway set out on voyages that would eventually result in their arriving as the first Europeans to explore the east coast of North America. Vikings established settlements in the Shetland Islands, Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Today in L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, there is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that reveals where the first Europeans had contact with the New World. L’Anse aux Meadows Heritage Site dates back more than 1,000 years and 500 years before Columbus, indicating that the Vikings have been an integral part of Newfoundland’s Heritage from the very beginning of man’s ancestral wanderings.

Oil In Norway

In the late 1950s, very few people believed that the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) might conceal oil and gas riches. It was the discovery of gas at Groningen in the Netherlands in 1959 that caused people to pay attention to the petroleum potential of the North Sea.

In October 1962, Phillips Petroleum sent an application to the Norwegian authorities for exploration in the North Sea. In May 1963, Einar Gerhardsen’s government proclaimed sovereignty over the NCS. New regulation determined that the state owned any natural resources on the NCS, and that only the king (government) is authorized to award licenses for exploration and production. The first licensing round was announced on April 13, 1965. Twenty-two production licenses for a total of 78 blocks were awarded to oil companies or groups of companies. The production licenses gave exclusive rights for exploring, drilling, and production in the licensed area. The first well was drilled in the summer of 1966, but it was found to be dry.

It was the Ekofisk discovery in 1969 that spurred the Norwegian oil adventure. Production from the field started on June 15, 1971, and, in the following years, a number of major discoveries were made mostly by foreign companies dominating oil and gas plays.

Norwegian Economy Advances

Statoil was created in 1972, and was the driving principle of 50 percent state participation in each production license established at the time. Provisions later changed to allow for varying degrees of participation in oil activities, and their progress and project participation became an important element of the Newfoundland government’s involvement in projects. Newfoundland was influenced greatly by Norwegian offshore oil industry regulations and regimes, as well as the Atlantic Accord, which governs oil exploration offshore.

Petroleum activities have contributed significantly to economic growth in Norway and to the financing of the Norwegian welfare state. Through over 40 years of operations, the industry has created values in excess of NOK (Norwegian krone) 12000 billion in current terms.

Since the petroleum industry started its activities on the NCS, mega-investment in exploration, field development, transport infrastructure, and land facilities has taken place. At the end of 2012, expenditures and investments amounted to NOK 3000 billion. Investments in 2012 amounted to over NOK 175 billion.

In spite of more than 40 years of production, only around 42 percent of the total expected resources on the NCS have been produced. Production (including NGL) reached a peak in 2001 of 3.4 million barrels per day. In 2012, the liquids production was 1.8 million barrels per day. Gas sales in the same year were 114.8 billion cubic meters. There are 8000 km of offshore gas pipelines with landing points in four countries in Europe. Fifty-three companies are currently licensees on the NCS and forty-two exploration wells were drilled in 2012.

Today Statoil has offices around the globe and their largest activities remain in Norway. Headquartered in Stavanger, Statoil maintains operations in both Stavanger and Oslo. Statoil is the largest operator on the NCS, and a license holder in numerous oil and gas fields in the region.

An Energy Affair

Much like Norway, Newfoundland, twenty years later, produced the first oil offshore with the Hibernia Platform. While wells were drilled in the early 1960s, economic obstacles had to be overcome before the first significant discovery was found in 1979. By 1991, Hibernia, the first of several offshore projects, was signed and given the green light for the construction of the Hibernia platform—a gravity-based structure (GBS). Valued at $5.2 billion worth of construction work, this gravity-based and topside assembly was an unprecedented engineering feat like no other. The GBS and topsides were towed 250 miles offshore—a concrete island living in the ice infested arctic waters of the Atlantic Ocean. The first offshore oil for the province of Newfoundland and Labrador began there in 1997.

Like the phoenix rising out of the ashes, a new industry was to emerge offshore Newfoundland. Nobody truly comprehended the impact or the magnitude, but enthusiasm energized the government and business community to create an oil and gas industry over the course of the next twenty years.

Today, we can see the similarities of development in the North Sea emerging offshore Newfoundland in the Jeanne D’Arc Basin and now in the Flemish Pass Basin. Calling on primarily Norwegian and U.S. technology advances, the Newfoundland oil industry grew from Hibernia into more fields such as Terra Nova, White Rose, and Hebron—with more to come.

Statoil Strikes Again

StatoilHydro currently owns interests in several exploration, development, and production licenses offshore Newfoundland. StatoilHydro is also a partner in the Hibernia and Terra Nova fields as well as a partner in the developing Hebron field.

Newfoundland and Norway are continuing their joint petroleum efforts as stated by the most recent oil announcement in October 2013, with the revelation of potential reserves in the Flemish Pass Basin where hydrocarbons were encountered while drilling the deepwater Mizzen prospect.

Statoil, which is 67 percent owned by the Norwegian government, said it is closer to commercialization after uncovering a field holding between 300 million and 600 million barrels of oil at its Bay du Nord prospect in the Flemish Pass Basin, offshore Newfoundland.

The Norwegian-Newfoundland legacy continues. Ties are strong, and the influence and contribution from both entities abound. The Mizzen prospect is a new find, a new play, and a new bridge linking Newfoundland to Norway, further cementing the alliance.

Did you enjoy this article?

Surveying The Road To Project Success

Surveying The Road To Project Success Atlantic XL - Big Name, Giant Vision

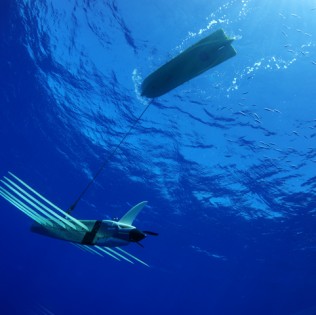

Atlantic XL - Big Name, Giant Vision Autonomous Marine Vehicles [Liquid Robotics]

Autonomous Marine Vehicles [Liquid Robotics] World Leading Exploration Site: A Paradise For Pioneers

World Leading Exploration Site: A Paradise For Pioneers Canada’s Liquefied Natural Gas Potential

Canada’s Liquefied Natural Gas Potential