by Tony Morley

Published on April 1st, 2014

Arckaringa Basin

It would have been nearly impossible to predict that this visit to the desert would yield anything abnormal, anything significant. This was intended to be a routine field deployment. I had not the faintest clue that I was about to become part, albeit a small part, of an extremely large discovery.

In early 2011, the call came in to lend a hand on a remote crew working roughly eighty kilometres outside the desert town of Cooper Pedy. This small, parched collection of desert hovels lies directly in the heart of the Arckaringa Basin and is a staggering 846 kilometres from Adelaide on the south coast of Australia.

It is within this Carboniferous basin that Linc Energy was scouting to prove the scale and viability of economical oil deposits. I would soon be joining a seven-week tour with a team of seismic surveyors mapping the subsurface of the region.

I begin my journey on a light aircraft that punches through a high layer of thin wispy, clouds, and I get my first look at Cooper Pedy, the landscape is pot marked by literally thousands of tiny mining shafts. From a thousand meters, it looks as though I am peering at an endless sea of ant holes. However, ants have no role in the creation of these holes. Long before anyone thought to look for oil in the region, there was a resource boom of an entirely different nature, a mining boom.

Opal is shockingly and arrestingly beautiful, a gemstone that shimmers like a kaleidoscope; the light literally dances off the tiny spheres contained within this rare mineral. Opal is also tremendously expensive; gem quality opal is often significantly more valuable than diamond. Opal was first found in Cooper Pedy in 1915 ,and it kicked off a resource boom that would eventually transform the region.

My aircraft lands into the sweltering heat of midday, and I am dripping with sweat and struggling with bags when I am approached by a man in a cut-off shirt and a wide-brimmed hat. He greets me with a strong handshake. “I’m Ben, but you can call me Kats, I’ll give you a hand with your bags, mate.” I like this guy already, he is tanned dark and rough as sandpaper, and it is clear this isn’t his first week in the desert. We pile into the back of a four-wheel drive and make a short stop before leaving behind the baking tarmac and scattered opal shops. “It’s the last opportunity for, well, anything; it would be wise of you to stock up on things you might require that can’t be made from spare parts around camp,” says Kats. “Like what?” I probe a little to see just how bleak this camps is really going to be. Ben responds with a grin. “Toothpaste, chocolate, and any other creature comfort you might like. Skip the booze, unless you’re keen to get sent back on the same plane from which you came.”

In the last twenty years, Australian hydrocarbon reserves have grown from strength to strength with proven reserves of oil and gas growing steadily each year. Australia was the second-largest producer of coal in 2011 and the third-largest producer of LNG in 2012. The resource picture of this country is on a steady track, and that track is upward.

Looking back on the expedition, I think I would have had a greater reverence for the trip if I had known that we were actively engaged in part of the discovery of some 3.5 billion to 233 billion barrels or probable oil reserves. Initial value estimates were generated by the media by multiplying the resource estimate against a prevailing oil price above 95 USD a barrel and arrived at a shocking total of some 20 trillion USD. Linc Enercy Chief Executive Peter Bond was quick to correct the media, noting that the mathematics of this particular play were not as straight forward and as simple as grade school multiplication, and it was still too early to speculate on the actual value of the licences held by Linc.

After a short resupply, we gather the remaining parcels and parts for the field crew and make our way out of Cooper Pedy and toward our camp nestled about an hour outside the town in a natural desert clearing. I arrive in camp late and exhausted; it takes all the effort I can muster to get a bit of food and collapse into bed.

I awake the next morning to one of the brutal ironies of the desert; it is only a few degrees at 5 a.m. and a slight wind creates a biting chill that is quickly corrected with a heavy jumper.

This seismic crew is already in full swing; they have been out here for weeks and have already surveyed hundreds of square kilometres of stony, rough incendiary hot desert. Kats is unloading supplies from the back of the truck as I wave hello on my way into the HSE office.

Seismic surveys provide an invaluable glimpse into the hidden world of subsurface geology, a fact that sometimes seems lost on those members of the team who toil to layout and collect the kilometres of cable required to collect the data.

Despite the outback feel of the project, I am not allowed to so much as set foot outside camp until I am given a project induction, camp induction, contacts list, emergency response briefing, PPE examination, and the list goes on. If they were not a safety-first company, they were sure hiding it well.

Out on line I observe the crew’s meticulous layout and collected cable, the pristine remoteness broken only by the many tens of thousands of flies desperately attempting to drink the sweat from my skin and the saline water from my eyes. I have said it before and I will likely say it again, the men and women of seismic are often the unsung heroes of the hydrocarbon story. I would have imagined it might have put a small spring in their step if they had of known what lay beneath the countless rolling anticlines and thorny shrubs.

If the upper-end estimates are correct then it stands to reason that the Arckaringa Basin will have become one of the largest onshore oil deposits currently known. To put the potential of the Arckaringa Basin in context, Saudi Arabian reserves are estimated at approximately 263 billion barrels.

Shortly after Linc Energy released their initial resource estimates, their stock price jumped nearly thirty percent, and for good reason. Linc had continued to maintain a solid financial position while developing their drilling programs and receiving greater clarity on the nature and volume of hydrocarbons locked deep below the Australian desert with each passing year.

However, it almost goes without saying that there are considerable challenges that lay ahead before economical oil can be shipped to market. Linc will need to ensure they find a suitable partner to help them develop this outstanding resource and to develop a comprehensive plan for operating successfully in this water-parched and environmentally sensitive region. All of these considerations must be added to the challenge of installing the required infrastructure. However, it is far too early to hedge any bets against this project; the deck is simply too well stacked to their advantage.

I arrive back in camp tired and hungry, thankfully the food is plentiful. It is barbeque seafood night and all eighty crew members are dining outside just after sunset. Once the sun goes down, the flies leave and the temperature eases slightly; everyone unwinds and plans the next day ahead. Maps are updated and printed for the next morning; clothing is cleaned, and vehicles are cleared of dust and restocked with fresh drinking water for the next day. A small campfire of deadfall wood, collected from a small woodland in the distance, burns late into the night.

By morning we are huddled around the coals attempting to extract what little warmth remains. I kick off the morning safety meeting with an environmental talk about the flora and fauna of the region, and why it is so critical that all vehicles stick to the approved tracks. It is always best to leave as light a footprint as possible; although we don’t see it in the daytime, the desert actually teams with life. However, almost all that life won’t come out till after dark. Assisting the crew in developing a fond respect for the region helps to safeguard the area from inadvertent damage or disruption.

Exploring for oil in Central Australia is so completely different from any field in North America that it is almost unfathomable. The daily challenges of the desert are extraordinary, from the scorching heat to the coarse sand and from the snakes to the vegetation; everything in the desert is most unwelcoming.

Bull dust is another part of everyday life in the basin. A fine powder as fine as talc works its way into the smallest gaps, clogging computers and engine intakes, and destroying cameras.

A week before I am due to leave, the heavens open, covering the ground in a blanket of fresh rain. The rain shuts everything down, vehicles can’t move and our water truck can’t make it to the well bore about an hour distance from our tiny camp. Our only source of water, an eleven thousand litre water bladder had only just burst the morning before. I remember it clearly; I emerged from my bunk to brush my teeth and stepped into an inch of water. As flowing water in the desert is not a normal facet of my daily life, it came as something of a surprise. I peaked around the bunk building to see the remainder of our water pouring across the desert. With the entire camp on the most stringent water rations following our water reserve failure, it felt as if it went without saying that the desert is a truly challenging place to work.

As my portion of the project came to a close, I left behind eighty men and women who would have to wait months to learn the fruit of their labours and the magnitude of their discovery. For weeks the data was collected, and for months it was carefully processed and assembled. The resulting data helped to paint an almost entirely unexpected story, not only of Australia’s deep geological history but also of the future of Australia as a hydrocarbon resource power and of Linc Energy as a major player in the resource sector.

I am not much of a gambling man; however, if I were betting on Linc Energy, I would be pushing all my chips across the table.

Did you enjoy this article?

8 Great Women’s Organizations - Making All The Difference

8 Great Women’s Organizations - Making All The Difference Jim Keating of Nalcor Profiles the Exciting Exploration Opportunities Offshore Newfoundland & Labrador

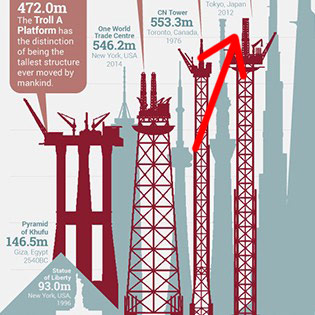

Jim Keating of Nalcor Profiles the Exciting Exploration Opportunities Offshore Newfoundland & Labrador How Tall are the World’s Largest Offshore Oil Structures?

How Tall are the World’s Largest Offshore Oil Structures? Here’s Why Global Oil Companies Are Investing In Offshore Newfoundland

Here’s Why Global Oil Companies Are Investing In Offshore Newfoundland The UK-Canada Love Affair

The UK-Canada Love Affair