by Tina Olivero

Published on January 4th, 2014

Planet Walker John Francis - He Stopped Talking and Started Walking and Then he Changed the World!

What makes a man decide to give up his car and walk everywhere he goes?

What makes him stop talking for 17 years in the interest of truly listening?

How did he earn degrees and teach without talking or driving?

What is he implying by his actions?

What is he teaching himself and others?

These were the questions that people naturally asked when they came into contact with John Francis during his silent tenure and walks around the planet.

The answers they got were thought provoking, bold, and transformative.

Oil Spill Leads to Action

In 1971, in San Francisco Bay, an oil spill of 800,000 gallons devastated the waters and natural habitat of the Bay. Two Standard Oil tankers, the Arizona Standard and the Oregon Standard, collided resulting in the largest oil spill in the Bay Area history.

The result was a growth in activism against pollution, whereby environmental organizations banned together for the oil spill cleanup, and a large number of Bay Area residents volunteered to clean up beaches and rescue over 4,300 oil-soaked birds—of which only 300 survived.

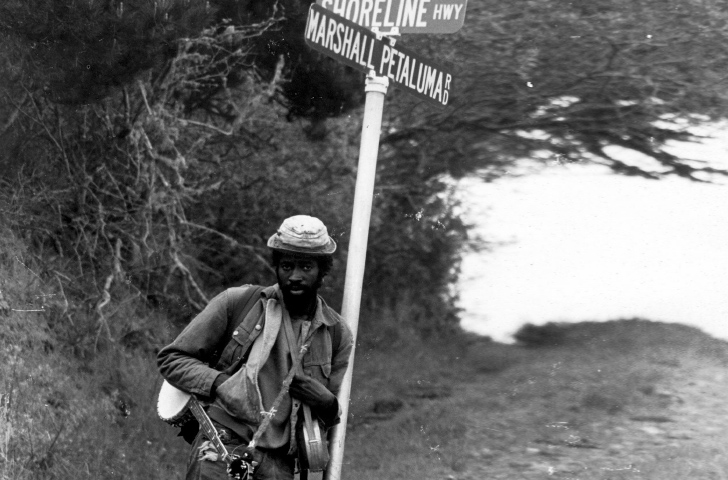

Nicknamed the Planet Walker

John Francis was born in 1946, arriving as a force of change and inspiration for a sustainable world.

John became an environmentalist when he saw the damage caused by oil spills, and was confronted with the loss of life that they caused.

He decided to react to oil spills and pollution in radical ways. For 22 years he refused to ride in motorized vehicles, so that he was not part of what was contributing to the pollution of our planet.

As John traveled the United States on foot, people would sometimes stop to talk to him about what he was doing. He found himself explaining and justifying a lot. He often found himself arguing with them about his decision to traverse by foot.

John describes himself as having an overinflated sense of self-importance at the time, and says that he initially expected other people to follow his example and stop using automobiles and other powered vehicles. This didn’t happen, but what did happen shaped the course of John’s life and touched hundreds of thousands of people around the globe.

During his walking tenure, he earned a PhD in land management and traveled extensively, walking across the entire width of the lower 48 states of the USA, as well as walking the length of South America.

Generosity

John explains, “As I walked across America, I earned money along the way playing the Banjo, working in print shops, and building and working on wooden boats. People were very generous and supportive. I would walk into a town, and it might have taken me five days to get from one town to the next. And when I got to the town, I would go to pay for my meal at the cafe, and they would tell me that it’s been paid for days ago. That happened more times than not, people would pay for my meals in advance. People would see me walking across the state and think ahead.”

Silence is a Virtue

On his birthday in 1973, John decided to stop speaking and instead to listen to what others had to say. He found this so valuable that he continued to be silent the next day. This continued day in day out, and he ended up not speaking for 17 years.

John relates, “The day I decided to become silent was a very happy day, and a very sad day for me. The sadness came from all the learning I had missed from not listening in the past. The happiness came from knowing that from this day forward, I could listen to others and gain a new understanding of the environment and the energy industry.”

John explains, “What was profoundly clear to me during my travels and education was that oil is a resource. We all use it—it’s abundant, and it’s a good thing. We depend on it. Each one of us has a responsibility to keep our planet clean and sustainable. The environment is a human concern.”

John recalls, “As part of my research and education, I learned more about the effects and prevention of oil spills, and, when the Exxon Valdez oil spill happened and it impacted the world, I was at the right place at the right time. My work on oil spill regulations not only supported environmental inquiry, but it also helped support those oil companies that had a strong sense of responsibility toward oil spills. People need to understand that accidents do happen. As long as we use oil, some of it is going to spill.”

How We Treat Each Other is How We Treat the Environment

John says, “How we treat each other is also how we treat the environment. So for example, if we exploit and oppress each other, those things will manifest in various ways in the environment as pollution, loss of habitat, and climate change. It’s an inextricable connection. We are a part of the environment and being conscious of that connection is critical to understand.”

John explains it like this, “The world is all us. People are not separate. The world is one world in which we all belong. When we take personal responsibility and take ‘care’ with each other and the environment, and we act in the interest of ‘all of us,’ then each of us will make the difference. There are many oil companies and other oil-related businesses that promote a culture of connection and oneness. That culture will translate into the way we work in the environment.”

With these realizations and a readiness to share them with the world, John ended his vow of silence on Earth Day in 1990 in order to become a strong environmental practitioner. He says, “I call myself a practitioner because we all work together, we do the best we can, and it’s a daily practice.”

While John was silent, he completed three college degrees, culminating in a PhD in land management from the Gaylord Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Before that he walked to Ashland, Oregon, enrolled in Southern Oregon University, and completed a BS degree there in two years. He received his MS degree from the University of Montana in Missoula.

John has been employed by the United States Coast Guard to work on legislation relating to oil transport and the management of oil spills. In 1991, he was named a United Nations Environmental Program Goodwill Ambassador.

In 1994, John decided he could be more effective if he again used motorized transportation. At the border of Venezuela and Brazil, he boarded a bus.

Geothermal Energy to Power Cities

John shares his ideas for energy of the future. He says, “I currently work as an ethical advisor of joint government and industry humanitarian efforts in dealing with disasters, and we evaluate the new technology that’s available to support those disasters. What we are seeing is an array of technology becoming available in the alternative energy sector, and it is very powerful. There’s very advanced technology, showing up in geothermal specifically, which looks like it’s going to be a game changer. Geothermal advances are moving forward to the point where it looks like we will be able to power cities and entire regions.”

A New Energy Mix with ALternative Energies

As John reflects on his one dream for the future, he says, “I’d like to see new alternative energies come online. It takes energy to do great things like eradicate poverty and hunger. It takes the wise use of the energy that we have and a plan to come online with new alternative energies that will do great things like end war, feed people, and create abundance and sustainable living. This is available to us now—it’s a matter of us being creative, efficient, and resourceful. What walking and not speaking has taught me is that when we listen, we learn. Let’s start listening.”

Education of the Future

The future of education is experiential and personally interpretive. John says, “At the Nelson Institute, we are developing ‘Semester on Foot,’ a program where our students can take programs walking the countryside. Students are assigned to specific communities and engage in community service as internships that are based in real-world experiential learning studies. Walking semesters allow our students to be out in the world learning about the environment, and, with the advances of distance-learning technology, they also remain connected to the university. It’s powerful because our students discover and engage with the environment in a way that is truly personal and intimate.”

Speak with Dr. John Francis

Today, John’s Planetwalk Foundation consults on sustainable development around the world and works with educational groups to teach kids about the environment. For more information on the Planetwalk Foundation or to book John Francis for an event or to learn more, please visit planetwalker.org. As a point of interest and a book you may be interested in reading, John Francis is also the author of Planetwalker: 22 Years of Walking, 17 Years of Silence, published by the National Geographic Society.

Did you enjoy this article?

The Unlearning Curve

The Unlearning Curve Rediscovering Black Gold

Rediscovering Black Gold Canadian LNG on Ice? Where Will the Puck Stop?

Canadian LNG on Ice? Where Will the Puck Stop? Paul J. Johnson – A Tribute to a Passionate Community Leader

Paul J. Johnson – A Tribute to a Passionate Community Leader